The poets lie too much, Nietzsche’s Zarathustra says and criticizes the poets for creating heavens and Übermenschen for their heavens, high-flying ideals and flowery language with which to approach a monster, trying to find meaning in life not through facing life squarely and then, from out of the womb of this confrontation, having arise an honest if meager meaning, but through dreaming, giving way to whatever nonsense happens to meet them in their cloudy apartments and lying on it like a bed, or holding onto it for dear life. He adds: WE lie too much, for he, too, is a poet. Only a fool, only a poet! is the lament heard even later in the work, on Zarathustra’s travels to a kind of enlightenment. He regrets having still to be a poet, and sighs when he says that on the great bridge human beings are crossing, between beast and Übermensch, he still figures as a cripple on that bridge.

This comes from the mouthpiece for a man who also mocked truth as anything attainable with more life, with more reality–than a dream. Dream on this philosopher said in his Gay Science, so we must ask whether and in what way there is irony in Zarathustra’s condemnation of the poets, and his subsequent lamenting of his own poetic position. We must ask whether perhaps Zarathustra, and Nietzsche, saw something, heard something in poetry that relates to truth, even to ugly truths? Poetry could be the only gift we have to approach the world, to hear what the world says and give our piece of song to its song. To hear it out, and be heard: that’s poetry. The eloquent and stirring phrases poetry, as well as the stuttering words and halting brevity poetry. Poetry all around, in every direction. Maybe we are weaving stories all along, maybe even the greatest positivism remains a poetry! Maybe Nietzsche’s fit of lamenting all this, since it is poetry all around, even what we find hard and unendurable, was a piece of bad manners! Maybe–if we want to affirm this life, however damnable it might all seem, however ghostly of a dream it is, however much cruelty and misdirection we are forced to endure–we have to affirm being poets! Being–fools!

On consumerism

On consumerism. From whom do we get the request, no, the demand to buy, getting persuaded and goaded into the act even when it is to our greatest disadvantage, even when we would be better off if not in saving or building ourselves, then at least in questioning the whole enterprise, of having to work more in order to buy more, of buying more then having to work more? Why, sellers, of course. And behind them marketers, and behind them stock-holders, and behind them rapacious CEOs, and behind them more mysterious men, cloaked in silence and silent decision-making, most of them men, fattening their pockets, if not with dollars then with data, enviable streams of numbers in domestic or off-shore accounts. And behind them? What force is it that pushes us into buying this or that, even buying our so-called necessities–buying water, for example–seeing in every purchase a promise, of escape or security, of a life like that fortunate model there, of dominion, the promise of having one’s house at last in order recollected with each ring? If it is anything, we have left the sphere of the merely human; it is a force that floats there, something of an atmosphere between us and the heavens, the between itself, like every great epoch of Being, like every great binding meaning.

Different Colors

You’re always going to find different colors

If you look long enough,

Whether it’s the light playing on the surface,

Adding colored shadows and shades,

Or the skin beneath the coat

Coming through because of the angle of our eyes,

Or some fantasy about rainbows,

About seeing them everywhere, rainbows,

Those magic transitions rainbows

The color is never precise,

Never definite but goes on in richness,

Goes on in depth and dimension,

Goes on something like a narrative goes on,

Colors telling a harsh story,

Colors of the oral tradition sharing epics,

Colors of the mockery of black and white,

Creative color chameleon color,

Called many different names color,

Called stupid names color,

Like the name of some nothing color,

Or the name of something more maligned than the name

Of nothing color,

Color of nothing, one woman said,

Her hair the color of cinnamon creme,

The other and the first in a room colored

Mostly like a dark green leaf,

Its carpet some fruit and earth at once,

Paintings on all four walls, many paintings many colors,

Many different ages of color

And the fading of color out into memory,

Into the white of a bomb-lit sky,

Into the rust of seasonal departures,

The rust of going nowhere,

The door, a solid door, a solid blue

Attacked from within by rainbows,

Falling apart at its rigid moody borders,

It’s true, it’s all just Maya,

The first went on, looking out the window with her friend

Out onto the colors of chores or adventure,

The colors of leave-taking,

Growing less and less familiar as the road endures,

The colors are nothing, really, but a landscape

Bright or dark as seasons are bright or dark,

No matter how stubborn or stark they are,

No matter how red the red,

No matter how orange the orange,

No matter how yellow the yellow--

You know, yellow is the darndest one,

She laughed with the second, her friend, yellow

Is the color my daughter uses to paint the sun,

But look at the sun! Have you ever seen such display

Of the disarray of any set notion of color,

I mean it’s fire, fire so hot it burns green-blue,

Fire of every color, conflagration of color!--

No matter how green the green,

No matter how blue the blue,

No matter how violet and violent the violet

The color of the roses of your aunt’s funeral,

Each one is really only a play that stays awhile,

Before the players get tired of their roles,

Adapt to one another’s parts

Or change the story all together,

Something of a story-teller color,

Leaning back in her rocking chair like a grandmother,

The other woman disagreed and made it known:

Color all the way down! Take off my color you find-- Red, take off my red you find the white-yellow-grey

Bone, take off down to the marrow--yellow-purple

Marrow, take off my royal yellow-purple,

The soot of cremation, the tapestry of grey cremation,

Take off my grey gown

To reveal the churning cauldrons of color's creation,

Dispose of the stars, get stuck for an eon

In what can only be called cosmic pudding,

Get stuck in the thick color of that for an eon

Before you rid yourself of its gummy tones:

There it starts again, like a sunrise

For tireless animals under the sun,

Coloring the earth with an entire spectrum of things,

Colors of sex and food and shelter,

There rises the inescapable

Color of things, story-teller

With endless time to pick up where she left off

In the parade, even after those gaps

When a little girl asks her mother,

Tugging at her hair the color of cinnamon cream,

Little girl in a grey gown, Mommy,

Where’s the color?

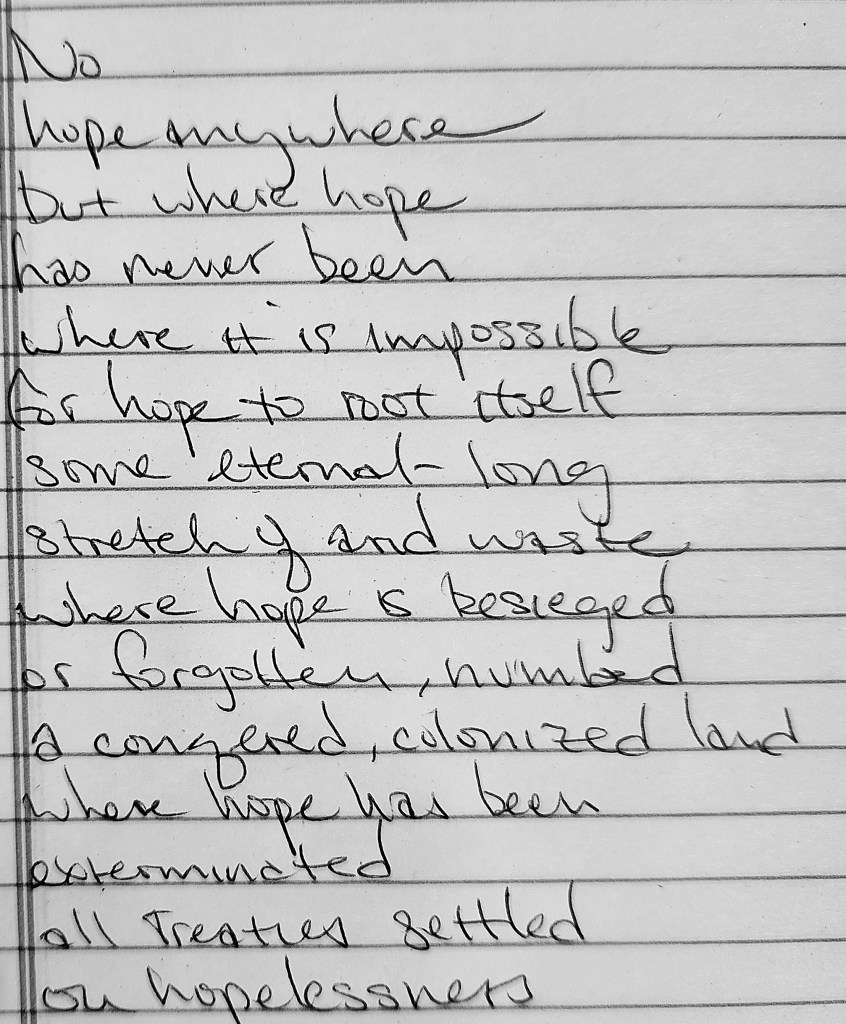

No (hope)

i don’t have to call you a god

i don’t have to call you a god

to respect you,

when i nod back to your flash

of orange, yellow and green,

hints of red that is enough,

when i promise not to catch you

with sticky traps and leave you

gasping in the night’s dew,

along with a palmetto bug,

a couple fellows of yours

and a taciturn anole,

that is enough,

when the sky does something

to light you so that i may see

your camouflage, and we eye one another

from the distance of two houses,

that is enough

when your stare lets me know

you’re there as my glance

tries not to frighten you,

you shy divine,

that is enough for me,

but for everyone, no,

they will throw your body

onto the sidewalk

to see it squirt and flatten,

that is enough for them

because they want,

joy of joys,

to see blood,

god or no god.

Obvious: Mystery

From this angle it appeared flat and round, a giant disc overhead, and no one knew what to make of it, not to mention what to say of it. It hovered above our city with no visible intention to leave, to fly or float away, whatever it was capable of. For now and for a long time–children were born underneath that disc, the young became old and died underneath that disc, entire families changed, history went on as it is wont, with suffering and triumph intermingled, but only with this difference: for generations there would be an eclipse of the sun, for four or five hours a day, because of the sheer size of the object above our heads.

Strangest of all, the televisions, the internet, the newspapers, the radio, all of them, those channels through which we try to learn about what is happening in the world or distract ourselves with the sheer enormity and vastness of occurrences on the earth, all of them were completely silent as to the mere existence of the thing, let alone any attempt at giving an explanation for its size, shape, and for the barely noticeable lights, noticeable only when it was pitch dark all around, that could be seen around the edge of the disc in an array of unearthly colors, as though a man mad with color and its hitherto unseen and unimagined possibilities had abstracted from his dreams an utterly new palette of nameless colors.

What do you think it is? I mean, I’ve lived here all of my life long, I’ve been married and I’ve had several children, all of them grown now. I never thought to ask, a woman asked me as we came out of the grocery store by happenstance, not because we had traveled there together. She was in a large purple and brown coat that covered the whole of her body, as it was more that a little cold, and, as she turned, looking like an oversized, human-sized plum with overripe brown edges, away from me and cocked her head up to the sky, where the disc was in its usual suspension above all of our cares and troubles, she continued: Has anyone ever dared to ask? We can’t go on living with such a blunt mystery. Mystery is always hidden, she said, so when it’s there–she pointed up, or at least the soft purple staff of her arm directed my gaze upwards with her–obvious in your face, that’s no longer mystery, and to live with it without asking what it is is not reverence or in any way a proper composure before what faces us in our lives.

She was on to something: indeed, she was the first citizen of our rather tightly-bound city–everyone there was part of a cohesive family, in fact, even though our population had reached over one hundred thousand a year or so ago–to ask any such questions or to make any such proclamations. I was dumbfounded when she asked, as I didn’t know for the life of me what to make of the thing up above. To be truthful, with you, because I know you are searching for truth like a good explorer, always and restless searching for truth, even in twisted metaphors, tangled stories, and indecipherable tropes, you can’t give up in your search, I wanted to simply shrug my shoulders and shrug off her questions like I wanted to put down my bags on the counter at home, perhaps make a sandwich after putting away the groceries and supplies I had secured, and set about other business, the more pressing affairs of the day-to-day. But as she was standing right beside me and as she wouldn’t budge, neither with her body or with her words, I felt obligated to attempt my form of an answer.

And this is what I said to her: Lady–well, I didn’t call her lady, I was more respectful than all that–Ma’am, Miss–something like that, although Miss implied a youth this woman had long left behind; she was old, old, old, her coat looked more youthful than her and that was not saying much, ragged and beaten and torn up as it was–Ma’am, I think I said, I think at least we have all dispensed with the dream that that thing–I pointed along with her, because her arm was as though stuck pointed up to the flat circle above us–was sent here, or traveled here due to any intention, in order to announce to us some message we could get in no other way. I think it’s fair to say that we don’t believe in extraterrestrials any longer, that that fairytale has long been thrown away along with grandfathers in the sky and our ancestors having some concern for us and tending to us, looking out for us, from their graves. It’s probably nothing special, or nothing to worry about in any case. You can rest well tonight as you have rested well on other nights. The thing has been here for your entire life, I reminded her. It was here that she put down her arm, or the purple arm dropped by itself, because of the great size and weight of the winter cloth, and seemed to be despondent because of my retort.

Something even fell from her bags, an apple or some other round fruit or vegetable, and she didn’t bat an eye when it fell, then rolled clear to the other side of the parking lot, as though propelled from within. She only put down the rest of what she was holding on the cold cement beneath our feet, then said to me: Look, youngster–it was true, at least this much was true: I was a good deal younger than she, and it more than looked it; you could hear it, you could guess it closing your eyes too–there are some things an old and tired lady like me cannot give up. She could give up on being answered questions as to the existence of God or the meaning of life or of history, sure, but how–she said it and almost spit when she spoke–how on earth could she not fret at night or otherwise about this huge circular thing above her head day-in and day-out. Are we being watched, she whispered.

I told her that of course we are being watched, but not by this thing up there, I reckon. That thing up there, I said to her, is probably as blind, as mute and as dumb as anything else in the sky, or beyond the sky. It has no care for us down here; of this one thing I can be sure after living with it from my childhood on, all my life, like you. Could that be true, she responded, again in a whisper, and, satisfied or dissatisfied with my answer, she didn’t let me know, she picked up her bags with great effort, sighed and heave then took off in one direction, the direction opposite of her fallen fruit, while I hugged my own bags closer to my chest, looked up one more time–it never moved, this thing, it stayed there like a stain on the sky–and went off in my own direction, not bothering even to look back at the old woman.

We Build, We Destroy

You should have told her

that we not only build

and wish to build like children,

but also destroy, like children

but many times like adults,

grown beings thinking back,

we crumble what’s not a toy.

Like the time in the room

when so much was destroyed,

it was a zone of terror,

there were blinking shards

of glass everywhere,

staring slivers, really,

shining witnesses.

You should have said Look,

I think we can brook this tendency;

after all, it gives us a chance

to create in perpetuity,

but this was stupidity,

too dense to the woes of others,

so you took another course.

Your eyes poked at me,

hoping for this sacred clash

to thrive, not to get blown away

like a poor, pitiable ash;

we had our remorse,

but it was nothing to pause over,

it was like a charred honey.

The woes of others are left alone

like building stones

their scarred flesh is like a tent

under which we can hide, a hide

for the nomads we’ve become,

who build for a day

until the herd leaves.

We embraced one another

while blood still tarred the walls,

while the walls were pockmarked with holes,

while the soles of our feet bled

because of all the broken glass;

we felt there was no other way to forgive

than by sharing some pain.

But how pain goes with the joy

has me pass you now as if in hiding;

I know there is a pettiness we have overcome,

that I could tell you, it would be fine,

but I decide not to: it would be too cruel,

to drag you along with the two of us

into our carnal vortex.

Why all this noise and frustration

Why all this noise and frustration,

the frustration of sound

when it’s coming out forced,

over so little?

Cancel out those pings and pangs,

the fiery jingle of the whole cacophony

and you hear life for what it is:

some sort of preparing silent riddle.

Not Murder the noise, but Let it be

there wherever it happens to be shouting,

like a man shouting in the street

and everyone turns confused to the man.

Let it be, the bleat of it all,

because behind even the braying

you hear when you put your ear to things

there’s the simpler saying of nothing.

Of Mirages and Soap Bubbles

He was disappointed, because he was in so much pain, and he wanted the pain to cease–without paying the price to make it stop. All the same, I told him what I thought best a human should hear when they are in pain: reality, and reality’s laughter. But when he made his way up the stairs I began to think Maybe he’s at home in mirages, maybe it makes no difference. Maybe he will chase after funny things all his life and, when the joke’s on him, he will have practiced enough at laughing at butterflies and soap bubbles that he will be ready to laugh of his own accord. Maybe I was too hard on him. Or maybe–and this is the hardest to bear, the hardest medicine to swallow–it doesn’t matter so much that my speeches about pain and pain’s necessity, about this being all we have, about how we should be thankful for what we’ve got or thankful for nothing, is as much mirage, is as much soap bubble and butterfly, as anything else. Maybe I shouldn’t have said a word to him; I should have left him on his way, left him limping through the house thinking whatever pain inspired. I should have left him to go swimming in reality’s pool, drinking of that pool, that pool that, if you approach closer, if you finally reach it to dive in, disappears, the way cheer disappears when it turns to sobs, the way hurt and cursing tears disappear when they turn to dancing, lithesome cheer.

Propless Imagination

I hope that what happens in the movies does not fool us into thinking that film, and the visual refinement of film, enhances our imagination. There is something else involved in the images of lonely, propless imagination. Take vanishing, disappearing: with the greatest computer graphics we see, yes, plain as day, someone disappear or vanish right before our eyes. But–imagine someone vanishing…. There is much more involved than the mere sight, no matter how believable the sight is.

Strange About-Face, or, With or Without Inventory II

Picture this: a man becomes fed up with it all, with life and not only his life, to the point of rage, lets the steam of bitterness build until he almost tips over, curses the insane stupidity of the world, but quietly so that no one could hear him unless he approached damnably near, which was rare, because for some time he kept his distance from the inquiries of others, kept away and alone from crowds large and small so that, in his sharp stolen privacy, he could inventory all the injustices he found in the world, count all the illnesses and take faithful note of all the blatant, unrelenting corruption. What did he do? Was it the predictable, like commit suicide or go for a joyride with joy in carnage through a band marching the parade, or through a holiday market, or some cheery or solemn time of a great many gathering in the square, some holy day, time marked off from the rest for memorial, dedication, and reorientation, or simply staying on the course? Or did he perhaps get on one of the news channels, or create his own channel on the video-sharing platform on the internet, so that he could bash this and flail that, so that he could rant without anyone stopping him, not even the spies for the many nations he slandered, on his own stage, which would turn out inevitably to be his bare bedroom, bare save a photograph of Nietzsche taped to the wall above the philosopher’s works, or from some street corner, for however long he could until the business owner, a woman dressed sharply in the latest fashion, coming out to smoke a cigarette rather unfashionably, told him You have to leave, you’re blocking my store and, with a smile sarcastically tender and teenage-like and unreasonably, said too Sorry, I’m just doing my job? Or did the spies and torturers for his own land or another actually catch him make one bilious post too many, or planning to some hackneyed coup with one too many rifles, and he was forced to while away a sentence of twenty-five years in a cold prison as a rather unimpressive prisoner, hoping all along he would exit life locked up with his own manifesto or tract, but instead came up the way he had come in, just another life churned and broken by the machinery, then spat out like a useless part? Or was he so distressed that he took to pharmaceuticals and the latest in psychiatry, complaining without break in a white office somewhere, the photographs of the doctor on the doctor’s desk, one holding a baseball bat, in full uniform and smiling, the other in mid-twirl, in the gown of a ballerina, about how vulnerable he feels and about how he has been made a victim of powers he could never hope to harness or control?

No, amidst all of these quite usual possibilities, or alternatives of response in the face of life’s nastiness and brutality, he did something else, something uncanny: he lived a life and only that, a life of conversation rich and inane among friends, shared fine and plain meals with others or enjoyed the meals alone, continued to maintain his home and go to work at three or four jobs, at all of which the bosses had some vague suspicion as to whether to take the man seriously, or if instead he is only playing a game and engaging in a ruse at the job, so full of smiles and jokes and jabs throughout the day. He even, after putting away what he could his hellish-long list of life’s ills, somewhere in a drawer in his room or somewhere behind memory, in those false drawers where, if things go into them, things disappear into an oblivion which is almost a forgetting, but is too deep to be called a forgetting, which is surface, surface all over, he spoke of life not with wrath and grumbling heaviness but only light cynicism at times, at other times you would think he had committed to life for the long haul and would endure the stress of living with supreme gracefulness, speaking of the human enterprise, shared by any living thing, of living amidst countless other powers as, not a travesty or something to bemoan, a gift given blindly, that is, as no gift could be given, to total and innumerable strangers. Though at times he seemed sluggish, this related more to the weather, to the dense humidity of the season than to some fated disposition, or indisposition towards life, at other and more times he seemed to dance over the pavement when he walked, his gestures were like that of dancers, even when he was asking the waiter in the local cafe to please fetch him another cup of coffee before his show starts across the street, before he gives life to the stage set set for the show across the street and set to start any minute, he waved his hand in the uncommonest of ways, parting the air around him, if it had threads or currents, with only the most delicate balance and mixture of body and gravity, he moved, even when in line at the movie theater or with his groceries, as though each step, though it meant nothing, meant everything as much as nothing when given its proper eye and proper art and heart or source, stood out because it was part, part always and forever, of a grand performance of other dancing things, the whole world itself dancing, and as a part the whole too, each moment like the spell under which every other was yoked in love. No one suspected of anything like a cancer of ill thoughts about the world inside the man, unless as in the case of his bosses frivolity could be considered such a cancer. He was well-disposed, this man of contradiction, well-liked by friends and the unfriendly alike, and was given over to enjoy life, if anything.

Where this happened cannot be said for sure, although Washington comes to mind, especially since, when it happened, this strange about-face, Washington, D.C. was in the midst of some simmering revolution and clash of contradictory powers itself, the whole town bubbled over with outcries and grilled at a low heat in resignation and slavishness in the face of what the world was becoming, a world more disastrous than even the former world, which defined disaster, either those or some madness or some nonchalance in between, one that maybe would every so often go to the computer keyboard, in loneliness but full of others and others’ voices nonetheless, to make some conspiratorial or self-help-like comment on a comment board, discussing in its cross-purpose manner the affairs of the day, which were many and in counting as the day went on. So it would make sense for the man we are recounting and who is capable of giving us a sort of inspiration for our times to have lived in Washington, D.C., and fairly recently at that. Still, it cannot be said for certain where the man lived. Come to think of it, it might not be certain either that the man lived, that he lived ever or at all. How could a human being suddenly move on from those curses that are bound to come and satisfy itself with some form of playfulness and jest with life and, seemingly, sometimes, at life’s expense? Wouldn’t there have to be some other motivation for the man, perhaps a bedrock illusion or his own stone of stupidity at the bottom of him, to continue in what he knows is more heinous than farce, not mere farce but culpability, crime? But no, if life has taught us anything, especially at our times, it is that possibilities, while cruelly so and often cruel, are inexhaustible, therefore surely the man charmed the earth at some time or other, although our times, again, seems best-suited for such a multifaceted character. Besides, he teaches us something else: that the greatest crime, take the crime Schopenhauer believed our existence, any existence, to constitute can be made into a comedy, in the decisive reversal of what Schopenhauer himself once pondered over, one somehow ruthless and therefore short-lived, no doubt, but a comedy nonetheless, a brilliant spark for the ages to come, or for all ages for that matter.

It’s Because, or, Imaginary Weeds

It’s because the plant turned this way in the sun, its tendrils reached out just so, that the father had

nowhere to go, got tangled up and could not reach his daughter, tangled as he was in green under

blue, over brown.

It’s because the bark of the tree was a light dusty gray that, against the gray sky, the driver, his little

hairs dancing as they’re able, holding his lover’s leg, does not see a differentiation of gray and make

it back on the road, keep the car from becoming a can disposed by some littering giant.

It’s because some six-legged red muncher munched his way along the road of the branch, stopping at

each vaulting pistil along the way, colorless but tasteful, the whole flower, and its surrounding

leaves, a structure of taste, that the salads suffered from lack of herb, for a generation the family

winced.

It’s because along our walkways, in rows like guards hired for duty, the trees and shrubs, like a fearful

family letting out a shake only with the passing wind, give us think our city green and convince us

that the vegetal’s alive and well, that it’s so easy to sell depravity as fortune, and the child stares at

her screen.

It’s because the hibiscus and the hyacinth did not bloom their milky oranges, their pastel pinks and

baby blues, that meaning on earth for a season took another turn, all reason could take the hue of

doom, and the woman could believe anything, really, she heard on the television, and would have

voted for a dead speaker with the right labels on it.

It’s because the canopy of the woods formed a room so pitch dark that any timid hiker would beg for

fireflies to blink like night-lights, that it was cut down for lumber and cut down to size, that the skies

are forced to shine maddeningly perpetual light, or given assistance by lamp lest sight be destroyed

and the man feels locked in a day.

It’s because growth remains growth, even of relentless spreading algae, flowering in the deep, that an

unwelcome greenery seeps into the blue, that the waters become unswimmable, that their sparkle is

dimmed, and other beings, water-beings, one by one suffocate and perish, the larger ones the faster.

It’s because the leaves were all brown at her feet, or rusty red, or blacker than the center of ash, and

long blown off the tree that wished to hold them for another month, because winter came early and

the winter was long, that she realized the disaster and whispered to herself on the lane No more, no

more.

It’s because soon enough there were no more plants, not even the desert shrubbery, save for the

mockery of them we have in plastic melted down to the shape of draping leaves and bracing

branches, they were all wiped out by the intense heat, by the intense cold, that the girl grew

philosophic at eating the apple her mother gave her.

It’s because the apple seemed to be from nowhere, grown from nowhere, like biting into the conquest

of nothing, like fallen seeds from nothing taking root in nothing, or taking root in some dream we

had to be alone, that the apples grow the way they do, that we may eat of the vapid fruit.

It’s because it was all so slow at first, tolerable and barely noticeable, because when things started

happening, when there was this rapid reduction of green and such consequences in ordinary life, that

we were shocked at first, but then in time adapted to the new planet we created, with its artificial

fate, its plastic trees and imaginary weeds.

The Weight of This One Thing

On Something Related to Lying

If I say that I have done something but haven’t yet–for sometimes I rush ahead, tie up loose ends to accommodate a conversation or to pass over what I consider inconsequential–it’s most important that I approach in the future what I have yet to do; this is a fitting challenge to myself, my own sense of commitment and promising, as well as a fitting correction of the initial omission. If the omitted remains omitted, that is, if the language is never learned or the book is never read, if the promise is never kept either in the past or in the deep future, then–then there is only one word for the omission, unless a mere dream is sometimes enough to fulfill a promise, unless a dream is sometimes all a person can claim as his own.

As Thick as Dreams

Sometimes daydreams are as thick as dreams

The voice you hear in them echos, a living voice,

You make a decision within their arena, vital

Decisions you don’t make every day or just any day,

The person inside them is dying but here she’s fine,

She’s vibrant, she has a lot on her sharp mind,

Not only for herself but for the country; she asked

Whether I could come with her to some rally

I said No, I believe resistance is more subtle

Or something to that effect as she gave harsh eyes

Asking herself without asking me how I could become

So insipid and so uncaring, like some lump really

Instead of a man, then we laughed casually,

She patted me on my hurt shoulder and that

Is when I woke, hurting my neck but not from the pain,

Woke because of how dense she was, her hand

More substantial than anything I am seeing now,

Anything I can put my hands on now; it is all thinning

Quickly, the air above me, the thick contents of the dream.