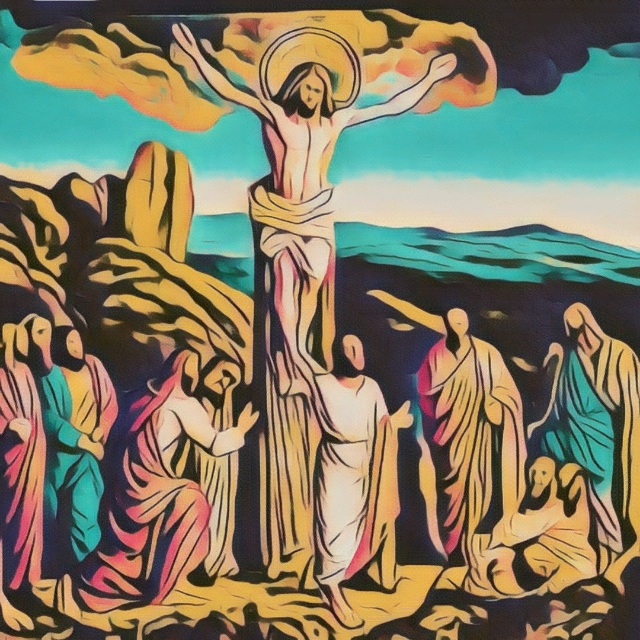

Christ is a haunting figure. And it is as though He were meant to haunt. His first gestures and words to His last were hauntings. It is His words especially that haunt. Fill the jars with water, He said, and the specters are still filling them to the brim, the wraith of Mary is still amazed. Give me a drink of water, and the ghost of the woman is still traveling though her town to tell her neighbors I have met the man who knows everything I have ever done. You could not remain awake for me, and the shadows of his disciples are still struggling for vigilance in that deep wood. Lazarus, rise! Now, though Lazarus has long since died, he remains there circling the tomb in regular spells, dismayed at having returned.

The Christ was meant to haunt. It is as though every other haunting is pale and insignificant compared to His archetypal haunting. It is a haunting–given flesh, and made to impact our flesh. Every reverberation of those words and gestures of Christ seems to confirm and reinforce our being spooked and taken in, as it were, by the ghost. Now, the figure of Christ can appear in hundreds or thousands of songs or films or animated series or pieces of theater, and they merely point out that if immortality is not eternity, it might be unto the end of the age. There is a way in which that ghost is here to stay. We are so thoroughly haunted that the denial of the ghost is another way to be haunted by the ghost, another and further haunting.

In fact, so deep is this haunting that there is a culture of the denial of holy things and all things spooky rooted precisely in being haunted. Haunted by specters that play and sing too close to the heart, this culture would rather they all fade away into doubtful images and lifeless propositions, while its own origin and staying power relies on the perpetual reanimation of these ghosts. The ghost of Lazarus, the ghost of the disciples, the ghosts of the Marys, the Samaratin woman’s specter, the centurion’s, his boy’s, Nicodemus’. All ghosts playing and singing around that archetypal ghost of Christ, that fleshly ghost and ghost of life, that Way of Life sent to haunt the living.

Christ is an inescapable figure. Once you’ve encountered Him, once you’ve been–spooked, that’s it. He stays with you, in all the cracks and creaks of things and even in the most voiceless moments. An inescapable haunting. Like the footsteps you have to hear in the abandoned halls of the earth since they are the footsteps of the house’s ruling spirit. Such a spirit cannot be exorcised or, if it could, it could only be exorcised by one and by one alone: the One with power over both the living and the dead. The most Haunting One. If that were to happen, if Christ were to finally deliver us from this haunting, maybe Lazarus and the Mary’s and all the rest would be free at last from forever spinning out their tales, but we, we…well, we would be lost, our sensitive hairs no longer standing on end.

(Un)Certain Truth(s) XI of XI, or, Judgment (enough)

(Un)Certain Truth(s) X of XI, or, Certain lines

Certain lines on a person’s face tell you that he is a philosopher, or that he was one at some time. Just as certain other lines on a face, or the absence of certain lines–more the absence–can make it apparent that one has never philosophized before, or that he is no longer a philosopher, or shall never be one, shall never philosophize.

(Un)Certain Truth(s) IX of XI, or, Justification

(Un)Certain Truth(s) VIII of XI, or, Stand corrected

(Un)Certain Truth(s) VII of XI, or, The Border Question

Between the Territory of Truth and the Territory of Falsity you will find the Border Question. It fences off one from the other, but only at certain times when the question rushes headlong into answers and convictions of all sorts. It can also challenge them and turn them upside-down, reimagine them or deny them altogether in favor of something more favorable, worthier of favor, more worth our day and our blood, it cuts or divides one from the other and makes each cut into or penetrate the other and spew its powers into the other’s belly, thereby making an offspring of the two camps, a veritable-mendacious Montague-Capulet. On the border there is the cut, the divide, the cutting into, the challenging, the interpenetration, the redefining and the denying all at once. At their respective edges, where they meet, truth and falsity are synthesized into what demands them both, into what needs them both.

(Un)Certain Truth(s) VI of XI, or, Truth themselves

For once, truth herself or himself or themself, depending on your love-affair with truth, truth itself, for what it’s worth, spoke out. The voice was nothing like a bell like some had imagined, at least nothing like a musical bell; if a bell at all, it was the sound of a cracked bell of a ruin somewhere whose song was ruined too. Truth said, Go on, say it–say it! Say what you are thinking, what your heart and head thinks: I am not what you were after and dreamed of all this time, you see what little manners and decorum, what little respectability I have when my mouth opens. You wish I hadn’t opened it; you wish I had stayed like all the best truths: tight-lipped.

(Un) Certain Truth(s) V of XI, or, Of the Philosopher

And then there was the truth of…. The man grew tired of cataloging all the eyes the sphinx has, how many ways there were to truth or how many truths there were. He revealed with his naming diverse levels of apprehension and intention, and could spell out in language approaching poetry–perhaps it was poetry, some kind of future poetry, a poetry of things to come, the interlacing of all things in a vast web–the worlds and lack of worlds of fish and horseshoe, of gnat and broom, of eagle and football field, of hammer and the rainbow eucalyptus. What a boon, his fellows thought, who would come to him four or five or more times a day to hear a couple of his truthful tales concerning the truth of things, a boon because, after all, it taught them to lockpick themselves out of their boxes to see what’s out there, and being relieved to find that there is something, that the world really isn’t just a dark room with dark walls, or a room lit to whatever brightness with the walls illumined accordingly, or a room with its walls painted in whatever fashion, landscapes or seascapes or skyscrapers be there as they may, however realistically. I just thought I sat on it, a man guffawed and remarked to the busking phenomenologist on the street corner, that is, he laughed when he heard that his stool at home was something more, richer and far more advanced in imagination than he had ever dreamed. Our scientist of the things themselves was too busy to engage with the passersby when they made jokes like this; well, with all he had to do, in giving an account of the waves of the multitude of things approaching him from their own multiple angles and speaking to him from their own multiformed lips. Contented enough with the street-philosopher’s story of being, the man who had stopped by on his stroll through the city to listen to a portion of the truths for a bit walked on, smiling as though he had received a gift, shaking his head and smiling, astonished by the greatness of the gift. Wow…the chair, he muttered, or the stool. Hearing of the lives of things described, or depicted–sometimes his gestures made us believe it could only be a work of art, it could only be performance–designated in such a way, this science of this vagabond, was a truly reviving thing for the human beings living in this inquirer’s company. Humans became rich enough in his company that, for once, they were no longer ashamed of their answers, that is, the answers that really mean something and get to things and are not just tools of some crude manipulation. Life on earth with him felt truly beautiful, and his truths, too, were beautiful, truly beautiful truths. For once truth and beauty could dance together, and goodness too, in a fine and noble dance. The world sang to and with this dancing, it was this dance.

Then a storm billowed over this faithful man one day, this man who had made it his mission to be faithful, with a type of grateful faith, to the things of life. The wise man fell asleep away from his wisdom and had a foolish and awe-inspiring nightmare or dream which told him thus: Truths, you say, it spoke in ghoulish tongue, but what else are they but crashing and shrieking chaos of ever-swirling, invested, ravenous, rapacious, ever-surpassing, and ever-belittling, forces? Parts next to parts and wholes next to wholes, and this forever and ever…. There is no reaching the end or finish as there is no reaching the beginning…. You present chunks of coal as though they are diamonds or diamonds as though they are coal, when really there is only coal or only diamonds, when all things are equivalent in this way, truth and falsity, truth and untruth included. What you say is what everyone says, what the liar says too, and your gifts are naught.

The philosopher did not know how to rebut his dream’s expressions and kept silent after that, thereby silencing all things. He remained this way for a long time, so long, in fact, that the city dwellers ended up forgetting about the man who had at one time had a tale to tell, a truthful tale about the world and what composes the world, they would pass him without so much as a glance in his direction. Silent he stayed, for days, for weeks, for months, for the exchange of quiet seasons eight times over, quiet in his breast, surrounded by all the bustling and fury of city life. A child came out of the dollar store with his mother one morning in winter, dressed in a tiny parka with bright blue cotton cuffs. He pointed through the icy air at the retired scientist, prodded his mother and said That’s him, right ma? That’s him? Huh, the mother asked her boy nonchalantly, then directed her inspection to the man through the drifts of fine powder drifting to the man. Oh, yes, that’s him alright. Or, he USED to be, she tried to explain, but couldn’t let out any more words before the boy let go of his mother’s hand and followed the hand he had outstretched to the man huddled against the lamp-post before him. Mister, the boy said boyishly but bravely, preparing to ask his own question, a question that really mattered to him. In the cold and empty as he was, all the man huddled there so could do was consider the child through the unsteady lens of his shivering. This was enough of a concession on the man’s part for the boy, so he asked, boyishly and bravely still, What’s this? He held out his black gloves covered in a light layer of white snow, and meant the snow, meant to ask about the snow. The man huddled there, the former extraordinaire in phenomenological description, knew this, because his account of snow was always one of his favorites, and he knew too how much the story would more than entertain the child, true and good and beautiful as it was. In his current mood, though, in this storm of his which was also becoming a snow storm for the whole city, as the snow was picking up now, the world was whitewashed now and indifferent to all the complexity beneath the blankets of hammering white. He couldn’t just ignore the child, but he couldn’t simply tell tales in his old way, either. So he improvised. Full of passion, droplets of tears turning into crystals on his cheeks, wasted but not so wasted as to give up on the education of the young, he reached out to the boy’s hand with both of his own and clutched it, the last warm thing in the cold, clutched it tight, squeezing it as though to tell the boy something beneath his words as a countertempo, something perhaps more hopeful, squeezed it tight and said That, he stammered, THAT, he chattered, is one of the most beautiful lies you will ever see, another beautiful lie. The boy’s mother heard the man share this ugly truth with her boy, grabbed the youngster and marched off into the cold, down the street, yes, but more into the cold, into the coldness of things, turning around once from a half-block away to give the man behind her a good scowling with the rigid lines of her mouth and squinted eyes. As mother was doing this the boy had his own reply to the answer of the man back there: he smiled to him, still huddled against the lamp-post, and waved in a friendly way, the snow on his gloves falling to join the rest collecting under his and mother’s feet.

(Un)Certain Truth(s) IV of XI, or, Due to its thoroughness and intensity

A: Well, you just made me feel stupid. B: Not half as stupid as I always feel. A: No, more than half, more than all of it, more than double. You made me feel really dumb out there. B: That’s not all bad. A: Why do you say that? B: Because stupidity is a virtue when you acknowledge it as your mark of distinction, when you feel your foolishness set you off from the rest, due to its thoroughness and intensity.

(Un)Certain Truth(s) III of XI, or, The whole truth

‘The whole truth.’ But what if truth is fractured and fractal, what if it is expressed only in riddles and ricocheting fragments? Then it would be ‘the whole side of truth,’ like admiring a building from its northern face. Truth something like a building: we could go inside, or around it, or walk a distance from it and view it from there, or visit another altogether. The whole city and skyline, the whole of architecture? What is that? Oh, what buildings we have yet to enter and roam the halls of, what buildings we have yet to build!

(Un)Certain Truth(s) II of XI, or, But truth hurts too

(Un)Certain Truth(s) I of XI, or, Veritas?

A Word about Words XIII of XIII, or, Our puzzle, our solution

The words were our puzzle, the words were also our solution, the key we needed to unlock, then to open and walk through, the cryptic, ciphered, indecipherable door we had spoken into existence. Where would it lead us, when finally opened and passed through. Into–more words? Into speechlessness? We had to say something about the matter, stuck in this one word as we were, as the jokester, or the cruel man, or the insane, loop a phrase over and over…. We needed them, these words, but what we needed we already had, we had it like the carrier carries his own antibodies, like the prisoner wears the key to his own cell around his neck.

A Word about Words XII of XIII, or, Words, words words, nothing but

Words, words words, nothing but words, wordiness and wordishness composing the world. The world seems so paltry when made up all of words and phrases and sayings, proper or improper or whatever. Until you reach out for them–not with your hand but, again, with words, with words like hands–reach them, touch them all over and realize that these things, these coughs and sputterings of ours, have more texture, more dimension, more weight and significance than the heaviest flesh, that even our most humorous or cruelest or insanest ramblings all have something to them that moves and shakes the world, provides its vectors and its center, or centers, of gravity. Words, words words, nothing but words, forever, eternally–humorously, cruelly, insanely.

A Word about Words XI of XIII, or, Questions for before, during, and after mealtime

Questions for before, during, and after mealtime. We bite into and chew and masticate words as we bite into and chew and masticate a cookie. How do they taste to us? How hard are they to chew, to swallow? How long do we have to leave them in the moistness of our mouths before they are softened enough to go down any further? How nourishing are they? Do they provide what we need, what is needed? Do they even fill us, are we even able to digest them, or do they make a struggling route through our intestines? How will they come out the other side? What will our bodies make of them, the bodies of them? What will they make of us? Will they come out at all, or will they be completely, utterly absorbed by us, incorporated into our fibers as water into soil? What might grow from that soil, the soil of us? A tree? How tall? A minute sprig? How small? A building, perhaps a tower or a tiny hut? A city, the ecosystem, life itself–the world?