He grew tired of asking questions, which was unfortunate, because those around him were waiting, and had been waiting, with utmost patience and devotions to hear the questions he would ask now, now that he was close to death. But what he wanted more, it seemed, was to banter, throw around jokes, to dance and sing and perhaps have a bit more to drink, other than that heavy draught he had taken a short while ago, that is, if it were allowed by the guards outside the room. These and he wanted to touch, to touch the men one more time before closing his eyes, before his conversation with Solon and Homer and the heroes of old, the shades. He was hoping, but didn’t put too much stress on it, that Crito and Phaedo and the others there would simply come up to him to give him a great hug, to let him smell one last time the oil and the earth on the men’s olive skin.

Xanthippe and the other women were allowed to stay inside as long, he said, as they played music together and sang together. This also helped the women with their tears, and Crito too, although as Crito danced he let out a couple streams from his eyes with the thought that he could tell Socrates that it was only sweat, that he was dancing and worked up quite a sweat!

Mnesarchus, little known but there nonetheless for saying goodbye to the dying wise one, finally broke the silence of the gathering and–asked Socrates a question. Socrates, he said, pushing himself from the wall where he had been leaning, listening, watching Socrates and thinking about him, then walking over to the man’s bedside, where Socrates, his legs growing a bit tired, had propped himself, upright, after a good dance with the young men, Socrates, you know I, more than anyone else here, would like to dance with you, join in the festivities and the celebration we are having of your life; such a life! But you know, too, how your disciples will be angered by this: not being able to hear you anymore, being without you, or what’s best of you. After your condemnation, how, your disciples ask, are we to remember you, you godless man whom no god remembers, how are we to carry on the secrets of what you have given us, especially as we are only singing and dancing and reciting poetry at your death! Who will be the one to preserve you?

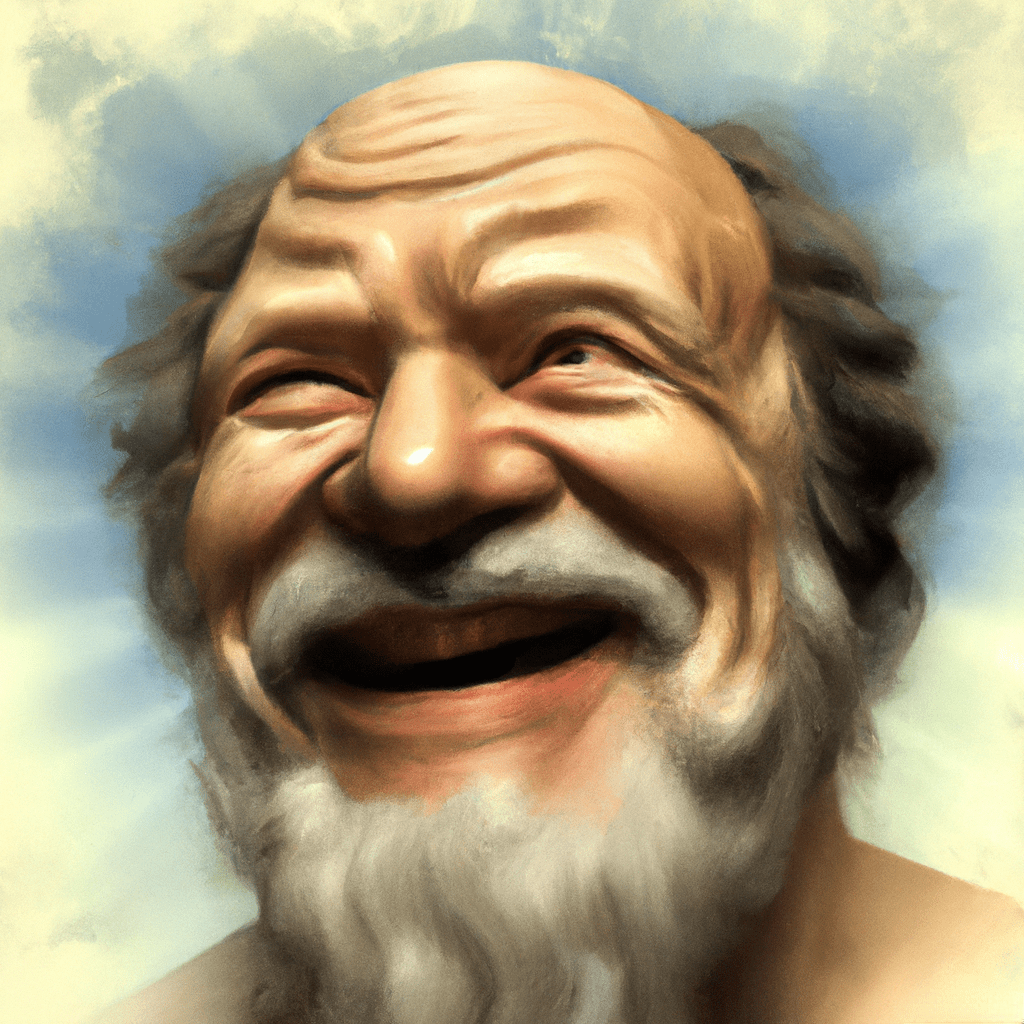

Socrates let loose a smile and shook his head in slight mockery at Mnesarchus’s question. But, although the ladies were just beginning a song he adored, although the men he adored were beginning to sway in response to the notes with their fit bodies, he felt he had to respond to Mnesarchus, as he has, although a spoilsport, always asked the questions that were most important, even now, even now when Socrates wanted nothing more, for himself and for the loved ones gathered there for him, to have dancing, drink, some merriment. Mnesarchus, you wickedly great fool, you! Let me say first that I understand your worries, they are good and true worries, although I’m unsure about their being beautiful. Earlier in my vocation, after having been asked with a strange irksome prodding to carry on as a lover of wisdom, I worried about such things. I asked What would be my legacy, or not my legacy, because one always disappears in the presence of great questions or is sufficiently challenged by them so as to keep things open, keep them amorphous and on the road, the way we had been so many times in our friendly conversations, what would be the legacy of these questions? I stayed up long nights asking myself and the dog such questions, questions my friends and I simply weren’t busy with, until it dawned on me: that will take care of itself, Mnesarchus, the way all things, ultimately, take care of themselves.

What do you mean, Socrates. Mnesarchus always called Socrates by his name and never Master, or Teacher or Instructor, sometimes even Holy Master or Holy Teacher the way the other young boys, those devoted as he, did. He knew that Socrates disdained nothing more than this display, and would rather be called by a nickname that is at the same time a jibe than one of these appellations. He thought Maybe Socrates heard something more from the priestess about immortality which he could share now, which would be relevant. Finally taking a seat next to Socrates, sitting close enough to him to smell the wine on his breath, the oil on his head and face and neck, he leaned over the more to put his arm around Socrates for a time, the time of that silence in which Socrates usually traveled when thinking and questioning.

There will come a one, Socrates went on, who will take care of this for us, but it might not be in the way you wish. He will have something, plenty, to say about me, and not everything he says will be accurate and most of what he says will, while being accurate and correct, sure, not get to the bottom of things, nor will they properly display a secret. This will be the legacy of the questions, in matters for debate and not as the magic that we experienced when called by a question, when called to one another to question. This writer, because he insists on writing, will be, like you, like more than a few others here on this occasion–different only in that he couldn’t make it–frustrated, embittered by the lack of gravity at the end of our journey, that it all turned to song and dance and light play and festivities, that it did not reach up to match the grandeur of some, of all of our previous investigations. He will get his revenge by writing such amazing pieces, most of which will have me as one of the dramatis personae, along with a couple others who are here now, amazing but they will have lost the wind, something important, in the conversations, in the time we spent together, and these works will be one of the only sources of my life afterwards. It will be impossible to know that I was more party-animal than others imagined, and that what I wanted most, more than to question, more than to discover truth or embrace wisdom, was to have a gay time with friends, and the women playing music, and the wine and frolicking of it all. I wanted this, and by the dog a big hug, before I died!

Mnesarchus heard this and gave Socrates what he wanted, hugging him not the way a boy or a man hugs his father, but with all the sensuality and tenderness a lover gives to a lover. They might have kissed, too, but Crito came over, oblivious of what had taken place, to pull Mnesarchus and Socrates into a roundelay. Mnesarchus got up from his seat with Socrates, asked him whether he wanted to join him in the dance, Socrates gave a big smile and said No, my legs are too tired, this dancing has worn me out, by the dog, Mnesarchus smiled a shy smile, nodded and joined the others dancing; Socrates, still smiling, laughing like a grandfather after one of his war jokes, lay down on his cot, and listened to the music become fainter, as he came upon not a light, but men and women, the wisest, gathered round a courtyard and–dancing themselves, all in bright colors! Wherever Socrates was then, he smiled.